Treasure Hunt: A True-Life Indiana Jones Saga

Treasure Hunt:

A True-Life Indiana Jones Saga

When you hear the phrase treasure hunt, you might imagine a chest of gold or a legendary artifact. But what if the treasure was a bird—and the hunter an ornithologist?

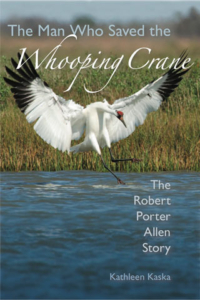

In the mid-1990s, I joined a field trip to Aransas National Wildlife Refuge on the Texas coast to see the endangered whooping crane. That experience changed my life. I became captivated by the crane’s story—and by the man who saved it from extinction. That fascination grew into a seven-year research journey and ultimately my book, The Man Who Saved the Whooping Crane: The Robert Porter Allen Story.

In the spring of 1941, the whooping crane population had dropped to just fifteen birds. Written off as doomed, the species survived because one man refused to accept extinction as inevitable. Robert Porter Allen, an ornithologist with the National Audubon Society, launched a conservation campaign unlike anything America had seen before.

Long before television or the internet, Allen ignited a nationwide media blitz. Posters flooded public schools. Children wrote letters to lawmakers. Radio stations tracked the cranes’ migration from their winter home near Austwell, Texas, to a mysterious nesting site somewhere in Canada. Life magazine published a rare photo of a whooping crane family, and even an oil company altered its operations to avoid disturbing the birds.

By 1947, fewer than thirty cranes remained. Their nesting grounds—hidden somewhere in northern Saskatchewan, possibly near the Arctic Circle—had never been found. Without protecting that site, the species would vanish. After two failed searches, Audubon turned to its most tenacious ornithologist: Robert Porter Allen, newly returned from World War II.

What followed was a real-life treasure hunt—one that helped save a species and changed the course of conservation history, ultimately paving the way for the Endangered Species Act.

The story of Robert Porter Allen is best described as Indiana Jones meets John James Audubon—and it remains one of the most inspiring conservation adventures ever told.

I wrote the book to pay homage to a man who was all but forgotten. My research led me on my own journey from Texas to Florida to Wisconsin and beyond in an adventure I like to call “On the Trail of a Vanishing Ornithologist.”

Excerpt:

It was April 17, 1948, in the early hours of a muggy Texas morning on the Gulf Coast. The sun at last burned away the thick fog that had settled over Blackjack Peninsula. The world’s last flock of wild whooping cranes had spent the winter feeding on blue crab and killifish in the vast salt flats they called home. During the night, all three members of the Slough Family had moved to higher ground about two miles away from their usual haunt to feed. The cool, crisp winter was giving way to a warm, balmy spring. The days were growing longer, and territorial boundaries were no longer defended. Restlessness had spread throughout the flock.

As Robert Porter Allen drove along East Shore Road near Carlos Field in his government-issued beat-to-hell pickup, he spotted the four cranes now spiraling a thousand feet above the marsh. He pulled his truck over to the roadside and watched, hoping to witness, for the first time, a migration takeoff. One adult crane pulled away from the family and flew northward, whooping as it rose on an air current. When the others lagged behind, the crane returned, the family regrouped, circled a few times, and landed in the cordgrass in the shallows of San Antonio Bay. It was Allen’s second year at the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. He had learned to read the nuances of his subjects almost as well as they read the changing of the seasons.

In the days preceding, twenty-four cranes departed for their summer home somewhere in Western Canada, possibly as far north as the Arctic Circle. This annual event, which had occurred for at least 10,000 years, might be one of the last unless Allen could accomplish what no one else had.

The next morning, when Allen parked his truck near Mullet Bay, the Slough Family was gone, having departed sometime during the night. That afternoon, he threw his gear into the back of his station wagon and followed.

The Man Who Saved the Whooping Crane was published by the University Press of Florida in 2012. It’s still available in bookstores upon request, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and University Press of Florida. It’s also from my website: Kathleen Kaska

Contact me at kathleenkaska@hotmail.com for information on my presentation of The Man Who Saved the Whooping Crane: The Robert Porter Allen Story

My second mystery novel,

My second mystery novel,