by Paula Gail Benson

It’s that time of year! Next weekend, the Agatha awards will be presented at Malice Domestic in Bethesda, Maryland. To celebrate, we asked the Agatha-nominated authors in the categories of Best Contemporary Novel, Best Debut Novel, and Best Short Story to tell us:

IF YOUR PROTAGONIST(S) COULD ATTEND THE AGATHA BANQUET, WHAT SHOES WOULD SHE/HE WEAR AND WHY?

Here are their answers:

BEST CONTEMPORARY NOVEL NOMINEES

Connie Berry

CONNIE BERRY: Kate rarely dresses up. She prefers jeans and boots—a wise move in the wet English weather. But when she does dress up, she always wears her 3” black sling-back heels. I haven’t checked her closet, but I wouldn’t be surprised to learn they are the only high heels she owns. She’s never mentioned any others. Besides, they’re perfect for her coloring. As a “winter,” Kate tends to wear jewel colors, especially red (it’s her husband, Tom’s, favorite color on her) along with black and white. To a recent dinner party at Finchley Hall, Kate wore a pearl-white satin skirt with a fitted black jacket—and her black sling-backs. Oddly enough, it’s just what I might wear myself. ‘ )

ELLEN BYRON: LOL! I love this question! Dee Stern would wear a really interesting pair of shoes or ankle booties that she either bought at a huge discount. She would have ignored the fact they were slightly tight when she bought them, figuring it wouldn’t be problem because she wouldn’t be on her feet that long. She would learn at the banquet cocktail hour that she was wrong. Limping by the time she reached her table for dinner, she’d kick off the shoes – and discover at the end of the evening she can barely squeeze her feet back into them. She eventually doesand staggers off to the bar in extreme discomfort. Or… what happened to me at a banquet happens to her. I bought this gorgeous gold sandals at a thrift store. They began to fall apart as the banquet went on, and by the end of it, they were in pieces. I wound up scurrying up to my room barefoot to retrieve my only other shoes, a pair of sneakers that did NOT go with my elegant dress at all!

Ann Cleves

ANN CLEEVES: Vera is very much more about comfort than style, but she would appreciate the honor of being invited to a prestigious banquet, so would make a bit of effort about her dress. I think she’d definitely be in flats, but they might be shiny patent leather. Or she would go for sandals of some description.

KORINA MOSS: Funny you should ask this question, because at last year’s Agatha’s when I was nominated for Case of the Bleus, I wore the shoes my cheesemonger protagonist Willa would wear—Keds. They are her shoes of choice, even when she wears a dress. In honor of her, I wore a long, flowy blue and white dress with light blue Keds. I felt I could get away with it because it’s what my protagonist would wear. I was so comfortable that I’ll be continuing the tradition at this year’s Agatha Awards banquet.

GIGI PANDIAN: Tempest Raj used to perform on stage as an illusionist known as The Tempest, so she’s used to dressing up in elaborate costumes. But now that she works for the family business, Secret Staircase Construction, where she gets to create architectural illusions like sliding bookcases and hidden libraries, she’s most at home in a T-shirt, jeans, and her ruby red sneakers. The new outfit is so much more comfortable! So for the Agatha Awards, I expect that Tempest would wear a long and elegant little black dress—but if she lifted the hem you’d catch a glimpse of her bright red sneakers.

Ellen Byron

BIOS:

CONNIE BERRY, self-confessed history nerd and unashamed Anglophile, is the author of the USA Today best-selling Kate Hamilton Mysteries, set in the UK and featuring an American antiques dealer with a gift for solving crimes. Like her protagonist, Connie was raised by antiques dealers who instilled in her a passion for history, fine art, and travel. Currently president of the Guppies, Connie lives in Ohio and northern Wisconsin with her husband and adorable Shih Tzu, Emmie. Her latest novel, A Grave Deception, is coming in Fall 2025. You can sign up for her very entertaining monthly newsletter at www.connieberry.com.

ELLEN BYRON is a USA Today bestselling author. Her Cajun Country Mysteries have won multiple Agatha and Lefty awards. The first book in her new Vintage Cookbook Mysteries, was nominated for Agatha and Anthony awards, and won the Lefty for Best Humorous Mystery. She writes the Catering Hall Mystery series (under the name Maria DiRico) and the Golden Motel Mysteries. She is an award-winning playwright and non-award-winning TV writer of comedies like WINGS, JUST SHOOT ME, and FAIRLY ODD PARENTS. Her website is Cozy Mysteries | Ellen Byron | Author.

ANN CLEEVES is an award-winning author, best known for Vera, Shetland, and Matthew Venn. All three have been turned into successful television series. Her nominated novel, The Dark Wives, was adapted as the very last Vera drama. The Killing Stones, which takes her character Jimmy Perez from Shetland to Orkney, will be published at the end of September by Minotaur. Her website is Ann Cleeves.

Korina Moss

KORINA MOSS is the author of the Cheese Shop Mystery series set in the Sonoma Valley, which includes multiple Agatha Award nominated books for Best Contemporary Novel and the winner of the Agatha Award for Best First Novel, Cheddar Off Dead. Listed as one of USA Today’s “Best Cozy Mystery Series,” her books have also been featured in PARADE Magazine, Woman’s World, and Writer’s Digest. Korina is also a freelance developmental editor specializing in cozy and traditional mysteries. To learn more or subscribe to her free monthly #teamcheese newsletter, visit her website korinamossauthor.com.

GIGI PANDIAN is a USA Today bestselling and award-winning mystery author, breast cancer survivor, and locked-room mystery enthusiast. She writes the Secret Staircase mysteries (locked-room mysteries called “wildly entertaining” by the New York Times), the Accidental Alchemist mysteries (humorous mysteries with a touch of magic), and the Jaya Jones Treasure Hunt mysteries (lighthearted adventures steeped in history). She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband and a gargoyle who watches over the backyard garden. For bookish fun, along with a free mini cookbook and free story, sign up for her email newsletter at gigipandian.com.

Gigi Pandian

BEST DEBUT NOVEL NOMINEES

Jenny Adams

JENNY ADAMS: Edie, one of the protagonists from A Deadly Endeavor, is a 22-year-old socialite in 1921. She’s a big fan of fashion (particularly of hats!) and she’d be thrilled to attend the Agathas! She’d wear something sparkly, beaded, and a little daring. As befitting the year, her dress would have sheer straps with a loose bodice, a swagged skirt, and a waist belted in a big bow at the back. Edie tends towards the dramatic–she’d probably choose a bright red, or a brilliant orange, with pumps to match. And since it’s an evening event, she’d choose a coordinating turban, secured over her wavy bob with a jeweled pin. She’d wear jewelry, too, of course; perhaps a diamond necklace and earrings.

Gilbert’s outfit is simpler: just like their speakeasy date in the book, he’d insisted on wearing his suit. Edie would try to cajole him into buying a tuxedo, but he’d refuse (they’re too expensive, and he’d have no other reason to wear it).

ELIZABETH CROWENS: Babs Norman, the protagonist of Hounds of the Hollywood Baskervilles, would wear a similar pair of shoes to what I’m going to wear at the Agatha Banquet, except that hers would’ve been actual vintage, and mine are vintage repro. Babs was a sensible gal and didn’t walk too well in high heels. Besides, how is a lady private eye going to run after or run away from a bad guy in heels? That only happens in the movies. Instead, she would’ve worn a black patent leather casual-to-dressy shoe with a two-inch wedge heel, circa 1940, of course, with a sling back closure and a slight peekaboo open toe. Fine for most of the year except during winter, and it would be something comfortable where she could be on her feet all day. Pssst, I bought these at Re-Mix on Beverly Boulevard in West Hollywood, and they are fantastic.

Elizabeth Crowens

Last year, I was on a panel at Malice Domestic called Clothes Make the Murder. We all dressed in vintage, and I helped provide hats for some of the other panelists. This year, for the Agatha Banquet, I also plan on dressing in vintage, similar to what my protagonist would’ve worn.

ELLE JAUFFRET: She would wear black Christian Louboutin stilettos because they are the most lethal-looking shoes she owns: elegant, sharp (the heel could be used as a knife—a reference to murder weapons in mystery novels), and the shiny red sole is reminiscent of blood. Plus, the brand is French, which matches her foreign accent syndrome.

JENNIFER K. MORITA: Maya’s best friend, Lani, would make her wear a pair of ridiculously expensive, impossibly high, “statement” stilettos, like Stuart Weitzman’s pearl-encrusted Bliss pointed toe pump, or the Moda slingback in champagne satin by Bruno Magli — borrowed of course because what writer can afford $800 shoes. But Maya would sneak a pair of “slippahs” in her purse for comfort.

K.T. NGUYEN: The protagonist of You Know What You Did, first-generation Vietnamese American artist Anh Le “Annie” Shaw would wear paint splattered designer combat boots paired with a fancy dress to the Agatha banquet. Eclectic and stylish!

K.T. Nguyen

K.T. Nguyen

BIOS:

JENNY ADAMS has always had an overactive imagination. She turned her love of books and stories into a career as a librarian and Agatha Award-nominated novelist. She holds degrees in Medieval Studies and Library Science from The Ohio State University and Drexel University. She has studied fiction at Johns Hopkins University and is an alumna of Blue Stoop’s 2019 YA Novel Intensive and the 2021 Tin House YA Workshop, and was a 2021 PitchWars Mentor. Jenny currently lives in Alexandria, Virginia with family, though her heart is always in the City of Brotherly Love. Her website is Jenny Adams – historical mystery author.

ELIZABETH CROWENS has worn many hats in the entertainment industry, contributed stories to Black Belt, Black Gate, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazines, Hell’s Heart, and the Bram Stoker-nominated A New York State of Fright, and has a popular Caption Contest on Facebook. Awards include: MWA-NY Chapter Leo B. Burstein Scholarship, NYFA grant, Eric Hoffer Award, Glimmer Train Honorable Mention, a Killer Nashville Claymore finalist, two Grand prize, and six First prize Chanticleer Awards. Crowens writes multi-genre alternate history/time travel and historical Hollywood mystery in Hounds of the Hollywood Baskervilles, nominated for an Agatha Award for Best First Novel (mystery), and Bye Bye Blackbird, its sequel. Her website is www.elizabethcrowens.com

Elle Jauffret

ELLE JAUFFRET is a French-born American writer, former criminal attorney with the California Attorney General’s Office, US military spouse, Claymore Award finalist, and Agatha Award nominee. New York Times bestselling author Jonathan Maberry described her debut novel, Threads of Deception, as “a powerful, complex, and compelling mystery,” and USA Today bestselling author Hank Phillippi Ryan called it “a smart and fresh new voice.” Elle is an active member of Sisters in Crime, Mystery Writers of America, and International Thriller Writers. She lives in Southern California with her family, along the coast of San Diego County, which serves as the backdrop for her Suddenly French Mystery series. You can find her at https://ellejauffret.com or on social media @ellejauffret.

Former newspaper reporter JENNIFER K. MORITA believes a good story is like good mochi – slightly sweet with a nice chew. Her debut mystery, Ghosts of Waikīkī, won the 2025 Left Coast Crime Lefty Award for Best Debut Mystery and has been nominated for the Agatha Award for Best First Novel. It’s about an out-of-work journalist who reluctantly becomes the ghost writer for a controversial developer. When she stumbles into murder – and her ex – she discovers coming home to paradise can be murder. Jennifer is a writer for University Communications at Sacramento State. She lives in Sacramento with her husband and two teenage daughters. When she isn’t plotting murder mysteries or pushing Girl Scout cookies, she enjoys reading, experimenting with recipes, Zumba, and Hot Hula. You can reach Jennifer at www.jenniferkmorita.com

Jennifer K. Morita

K.T. NGUYEN is a former Glamour magazine editor. Her debut psychological thriller YOU KNOW WHAT YOU DID has been nominated for Lefty and Agatha Awards. The Seattle Times called the novel “a swirly, tangled hair-raiser…as sinister as it is emotional.” It was selected as a People Magazine Best Book of April 2024 and named a Best Mystery and Thriller Book of 2024 by Elle, Parade, and Deadly Pleasures Mystery Magazine. K.T. enjoys practicing Krav Maga, rooting for the Mets, and playing with her rescue terrier Alice. A graduate of Brown University, she lives just outside Washington, D.C. with her family. Her website is K.T. Nguyen Suspense Thriller Books.

BEST SHORT STORY NOMINEES

BARB GOFFMAN: Ethan, the jelly-obsessed main character of “A Matter of Trust,” would wear the most comfortable shoes he has that go with the suit he would pull out of his closet, all the while wishing he could wear jeans and sneakers.

Hazel, the amateur sleuth from “The Postman Always Flirts Twice,” would wear a strappy open-toed shoe with a modest heel—the strappy shoe because that was in fashion in the spring of 1995, and the modest heel because she wants to enjoy the evening (being able to easily walk around listening to others’ conversations—should the need arise), and not deal with aching feet.

Barb Goffman

KERRY HAMMOND: Unassuming black leather shoes, she would want to blend in and not attract attention.

GABRIEL VALJAN: My protagonist is a member of law enforcement in rural Depression-era Tennessee. If he attended the Agatha banquet off-duty, he’d wear polished, well-maintained black leather oxfords or derbies to match his three-piece suit or dinner jacket. His shoes would be well-worn but cared for—remember, during the Depression, most folks didn’t have closets full of options.

If he were on-duty, the answer is a little trickier because uniforms for law enforcement were not standardized. Many sheriffs wore suits or slacks with a badge and carried their gun on a belt. As for shoes, I’m thinking something sturdy and durable for dusty roads, walking patrols, so sturdy black or brown leather boots with hobnail soles or leather soles with rubber heels.

KRISTOPHER ZGORSKI: The May/December relationship at the core of “Reynisfjara” means we would need two tickets to the Agatha Award banquet.

Bertram Bannister may or may not show up in a tuxedo, always one to prioritize appearance and perception. But he may not want to call too much attention to his attendance, so perhaps just a nice suit and tie to blend in. Either way, he’s likely to be sporting Brando Semi-Brogue Oxfords by Paul Evans. Luxury Italian footwear he picked up during his many travel escapades. Dress to impress is a motto this college professor takes to heart.

Kristopher Zgorski

Meanwhile, his new boyfriend—Ernst Ziegler (no relation to the famous actor)—will most likely wear the same black & white checkerboard Vans he pulls out of his messy closet every morning. Working on a student budget, new footwear was hardly a priority, but maybe that will change soon. Stranger things have happened. Whoever it was who said opposites attract might have been on to something, judging by these two.

BIOS:

BARB GOFFMAN is the 2024 recipient of the Golden Derringer Award for lifetime achievement, given by the Short Mystery Fiction Society. She has won the Agatha Award three times, the Macavity twice, and the Anthony and the EQMM Readers Award once each. She’s been a finalist for major crime-writing honors forty-six times, including twenty Agatha nominations (a Malice Domestic record). Her stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Black Cat Weekly, Black Cat Mystery Magazine, and many anthologies. She works as a freelance editor, often focusing on cozy and traditional mysteries. www.barbgoffman.com

Kerry Hammond

KERRY HAMMOND is a fully recovered attorney living in Denver, Colorado. Several of her short stories have been published in mystery anthologies and her latest, “Sins of the Father,” was nominated for an Agatha Award. One of her stories was featured in The Mysterious Bookshop Presents the Best Mystery Stories of 2023. She also enjoys creating downloadable Murder Mystery party games for BlameTheButler.com. Home | Kerry Hammond

GABRIEL VALJAN is the author of The Company Files, and the Shane Cleary Mysteries with Level Best Books. Gabriel has been listed for the Fish Prize, shortlisted for the Bridport Prize, and received an Honorable Mention for the Nero Wolfe Black Orchid Novella Contest. He has been nominated for the Agatha, Anthony, Derringer, Shamus, and Silver Falchion Awards. He received the 2021 Macavity Award for Best Short Story and the 2024 Shamus Award for Best Paperback PI Novel. Gabriel is a member of the Historical Novel Society, ITW, MWA, and Sisters in Crime. He lives in Boston and answers to tuxedo cat named Munchkin. Home – Gabriel Valjan

Gabriel Valjan

KRISTOPHER ZGORSKI is the founder and sole reviewer at the crime fiction book blog, BOLO Books. In 2018, he was awarded the MWA Raven Award for his work on the blog. Appearing in 2023, Kristopher’s first published short story—“Ticket to Ride”—(a collaborative work with follow blogger Dru Ann Love) won the Agatha, Anthony, and Macavity Awards. His second short story—“Reynisfjara”—is currently nominated in the Agatha Award Best Short Story category and his latest story—“Losing My Mind”—appears in Every Day a Little Death: Crime Fiction Inspired by the songs of Stephen Sondheim. BOLO BOOKS | Be On the Look Out for These Books

Clicking Our Heels – Do You Prefer Amateur or Professional Sleuths?

Clicking Our Heels – Do You Prefer Amateur or Professional Sleuths?

I’m delighted to welcome guest blogger and former CIA officer, Carmen Amato, to the Stiletto Gang. I think you’ll enjoy the intrigue behind her writing. See you in June! Debra

I’m delighted to welcome guest blogger and former CIA officer, Carmen Amato, to the Stiletto Gang. I think you’ll enjoy the intrigue behind her writing. See you in June! Debra  never been done before.

never been done before.

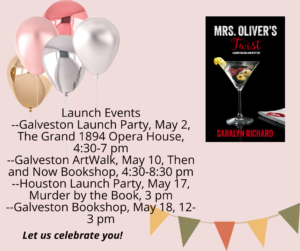

Please let us know your thoughts. And, of course, we look forward to seeing you at some of the book events this year!

Please let us know your thoughts. And, of course, we look forward to seeing you at some of the book events this year!