Writer, humanist,

dog-mom, horse servant and cat-slave,

Lover of solitude

and the company of good friends,

New places, new ideas

and old wisdom.

Susan had never told her family about her experiences. In fact, before Louisa Weinrib called her in 1990 for an interview, she she had never talked about what happened to

anyone other than those who had gone through it with her. Hers is a true story of

amazing strength, resourcefulness, and friendship.

Susan Eisenberg’s childhood was full of promise. An only

child, she was born in 1924 into a family that proudly traced their Hungarian

lineage back a hundred years. She grew up in the small town of Miskolc, where

her father had a successful business buying and exporting livestock and grains

for a farming cooperative.

Susan was aware of anti-Semitic sentiment, but it didn’t

touch her early life. The Jewish community was well integrated into Hungarian

society, and she had many Christian friends. She spoke Hungarian and German, loved to ice-skate and ski,

and wanted to go to college, but by the time she was of college age, Jews could

not attend.

Her loving and close-knit family gathered after synagogue at

her home, where they also celebrated the Seder. On weekends, they offered a

tradition of high tea for family and neighbors.

Trouble began in 1938 with a small Hungarian Nazi party that

grew in strength, paralleling the party’s growth in Germany. After Germany’s

invasion of Poland in 1939, Polish refugees fled into Hungary, bringing what

seemed unbelievable stories of what was happening in Poland. Without a birth

certificate validating birth in Hungary, officials shipped the fleeing

civilians back to Poland. An army friend confided to Susan that, in reality, the

Poles were taken across the border and shot. Even when people began wearing

brown shirts with swastika armbands and spouting slogans, Susan recalled, the

Jewish community just ignored it.

In 1940 Hungary became an Axis power. Hitler, who invaded

the Soviet Union in 1941, demanded that Hungary join that war. Susan’s uncle

died when he was forced to walk with others into a field between the German and

Russian armies to test for the presence of land mines. Her father was taken to

a work camp. Released the following year, he was ill and depressed and died soon

after at 44. After his death, Susan and her mother moved to the city of Budapest

to live with relatives.

Although the Jews in Hungary suffered under tightening

restrictions, Hungary’s regent protected them for a time from Hitler’s “final

solution”—extermination—until Hitler discovered the regent was secretly

negotiating an armistice with the US and the UK. On Easter Sunday in March

1944, Susan was having coffee with a friend on a cafe terrace and saw German

panzer tanks rolling over the bridges into Budapest. The Germans occupied and

quickly seized control of the country.

The Nazis rounded up her family members who were still

living in the countryside. The relatives sent postcards—which Susan and her

mother later learned the Nazis forced them to write—advising they were well and

going to Thersienstadt (a concentration camp/ghetto in Terezin). All of them

perished in that camp.

In Budapest, Allied forces regularly bombed the city.

Everyone carried bags of food at all times, never knowing when they might have

to run into the air-raid shelters. Jews were required to wear a yellow star patch

on their clothing and live in designated housing. Restrictions dictated when

they could leave the house and forbid them to go to public parks or even walk

on the sidewalks. They could work only in manual labor positions. Jewish professionals,

doctors and dentists, could only practice on Jewish patients.

Susan was 19, with light blonde hair and blue eyes. She pulled

off the yellow star from her clothes and snuck out into the country to get

food. Once, on her return, Germans soldiers in a vehicle, not realizing she was

a Jew, picked her up. They asked for a date. Heart pounding, she agreed, lying

about where she lived, and promised to meet them later. Safely home, she looked

down at her clothes and realized that a closer inspection would have revealed

the stitch holes from the star she’d removed.

When the Russian army was approaching Budapest, the

Hungarian Nazis ordered Susan to report for labor with her age group and sent them

to dig foxholes. Their Hungarian Nazi guards were 14 or 15-year-olds. When a

young girl working at Susan’s side sat down and cried for her mother, those

guards immediately shot her.

For two days and nights in the cold and rain, with no food, the guards ran them

back to Budapest to work in a brick factory where she met two girls her age,

Ferry (Ferike Csato) and Katherine (Katherine Goldstein Prevost). Susan pretended to be crippled and part of a group of sick and injured destined for

Budapest and death. She escaped and made it to her aunt and uncle’s house, but

the following day Hungarian gendarmes (police) rounded her up with others. The

gendarmes forced even mothers from their babies to join with those in the

streets.

Their Hungarian guards told them they were taking them to

Germany to die. “The one who dies on the road is lucky,” they said. Over a

ten-day period in October, they walked in rain, ice, and cold from Budapest to

the German border (125 miles) to Hegyeshalomover. Thousands were shot for

lagging behind or collapsing. A few country people along the way gave them a

piece of bread. Others stripped them of their clothes. Guards kicked them. They

slept in flea-invested hay.

Anyone who had anything of value traded it to the peasants

for food. They fought for a share of rare carrot or bean soup.

One night, the guards packed them onto a barge on the Danube

River. Overwhelmed by the press of dying people, Susan escaped by swimming to

the bank in the freezing river. She begged a man she encountered to help her or

just get her something dry to wear. He agreed but instead returned with police

who escorted her back to the prisoners.

At the German border, they marched another ten miles to

trains. Jammed into cattle cars, they traveled for days but couldn’t see out

because black slats covered the cars. She was only aware of repetitive stopping

and starting.

Finally, in October 1944, the trains arrived at Dachau

concentration camp in Germany, their destination. The smell of the crematorium

camp would stay in her nostrils for the rest of her life, as would the shock of

her first sight of the skeletal prisoners who mobbed them, begging for bread.

Guards beat the prisoners back.

The newly arrived assembled in a large open field, waiting

to go in. But even with bodies being constantly cremated, there was no room for

them in Dachau. Susan and her two friends, Ferry and Katherine, went with other

girls to Camp Two and then Camp Eleven (nearby work camps). They slept in

bunkers below ground on a wooden floor and a pallet of straw. Camp Two, they

quickly learned, was the “sick camp.” The next stop for Camp Two occupants

would be the crematorium in Dachau.

At the satellite camps, they were given striped uniforms.

About 500 people lived in each barrack with a block leader in charge. Food came

once a day in a big wooden barrel with hot water and big hunks of sugar beets.

At night they received a piece of bread that “oozed sawdust and a piece of

artificial marmalade.” At first, she couldn’t swallow it. The older inmates

encouraged her to “eat it, no matter what.”

Each day, the prisoners were called out to stand, sometimes

for hours, in the cold for a count and work assignments (Appell). “If you fell

out, you were beaten or shot. If a friend was dying, you made sure that she

stood up, no matter what, and wasn’t left in the barracks.”

In the first Appell, Susan was picked to work in a kitchen where

she peeled beets. Germans brought in prisoners for punishment, hanging them

from rafters and beating them. She and the kitchen workers constantly cleaned

the blood from the floors. She hid beets inside her baggy shirt and shared it

with her camp mates and the Muselmann—the starving, skin-and-bones

prisoners resigned to their impending death.

Susan was transferred to different camps for work

assignment. At one, German engineers of the Wehrmacht (Armed Forces), instead

of SS troops, ran the camp. More humane, their military task masters distributed

pieces of food to the workers, food that kept Susan alive. Barehanded and

dressed only in the thin striped uniforms and sockless wooden clogs, Susan and

her fellow prisoners pulled wagons of wood in the Bavarian winter mountains.

Sometimes she was taken from the camp to wash clothes for German housewives.

She also worked in the Sonderkommando (work groups at crematoriums) to

remove teeth from the corpses of the murdered for the gold fillings.

Her health was deteriorating. She had lost weight and

suffered from reoccurring high fevers. Typhoid broke out in the camp. There was

no medication. To isolate the prisoners, the guards stopped letting them leave,

throwing beets and bread over the fence.

In early March 1945, after the epidemics, a female guard

beat her for speaking defiantly to a camp commander. People all around her were

giving in to despair, but she refused to do so, vowing she would survive.

At another work camp, Susan joined women prisoners building

an underground airplane hangar. They were forced to carry 100-pound bags of

cement across a catwalk several stories high. The Muselmann went down

instantly under the burden, falling to their deaths. “There was,” Susan said,

“as much blood and flesh in that hanger as cement.”

An inmate orchestra played as she and other workers left the

camp and on their return. Guards made the orchestra watch and play during

beatings and hangings and while starved prisoners–who had tried to grab

potatoes from a wagon—were strung up between the electrical barbed wire, potatoes

stuck in their mouths.

Once, the Germans spruced up a barracks, putting in

furniture and stocking it with people they found “not in terrible shape” for

the Swiss Red Cross, who had come to inspect the treatment of prisoners. As

soon as they were gone, the Germans took the untouched piles of canned foods,

condensed milk, and chocolate the Red Cross had left for the prisoners.

One barrack’s occupants were expectant mothers. They were

allowed to give birth to their babies and tend them. Then one day, without

warning, all the infants were taken away and the women sent to the work

groups.

To use the open trenches to relieve themselves, Susan had to

walk through knee-deep mud at night, sometimes stepping on top of the bodies of

those who had fallen there and died in the mud. Survival, she knew, depended on

not allowing yourself to feel and thinking only of the moment.

Her last assignment was in a dynamite factory. By this time,

the air raids were almost continuous. Landsberg, a nearby town, was under siege

by the Americans. In April 1945, guards took her and her friends to the main

camp in Dachau. They spent a night in the showers at Dachau, believing they

would next be taken to the crematoriums, which were still “going strong.” But

the next day, with thousands of young people, they were marched out of the

camp. As they left, they could see the trains that continued to bring prisoners

from other camps [to keep the Allies from discovering them], many already sick

and emaciated. When the doors opened, dead bodies fell out. Inmates stacked

them like mountains in front of the crematoriums to be burned. But the Germans

had run out of time. The American guns were days away.

They marched from Dachau, walking at night and hiding in the

woods during the day. Allowed to dig in the fields they passed for roots and

potatoes, they ate them raw. All understood the guards’ orders were to march

them into the mountains and kill them in the forests where the Allies would not

discover their bodies. Guards shot in the head anyone who lagged or fell. Susan

was sick and feverish. She could not walk on her own, but three friends,

Katherine, Ferry, and another supported her, keeping her from collapsing.

As they struggled through the mountains and meadows of

Bavaria, guards began deserting in the cover of night. American planes flew low

enough Susan could read the insignia on the wings. The pilots, who surely saw

the striped uniforms, refrained from dropping bombs.

Five days later, what remained of their group arrived at a

work camp for Russian prisoners in the small German town of Wolfratshausen. The

first task of their remaining Nazi guards was to take the Russian prisoners of

war and shoot them. Knowing they were next, Susan lay on the roadside, too sick

and exhausted to react. Then she heard a roar—the first American jeep of the

Third Army coming down the road—liberators.

The German guards fled, but the liberators were combat

troops, unable to care medically for the freed prisoners. The Americans moved

on, and the liberated were left to fend for themselves.

Typhoid once again thinned their ranks. Her friends held out

tin cans for food the passing American soldiers threw to them. Survivors that

were able, brought supplies from the town and cooked soups. Reports that

Americans fed and clothed German prisoners, playing baseball and basketball

with them in the prison camps, ignited bitterness and anger. Many Jews took

abandoned weapons and hunted the German SS who had tortured them and killed

their friends and families.The sound of gunfire in the surrounding forests

peppered the nights.

They spent the summer in the woods, slowly regaining their

strength, then Susan, Katherine and Ferry trekked to a displaced persons camp.

Although her friends wished to immigrate to Israel, Susan wanted to go home to

Hungary. And they chose to go with her.

They walked to Prague, a journey of 145 miles, where a

Russian troop train allowed them to ride. Arriving finally at their destination

of Budapest, they found it devastated. Susan couldn’t find her house in the

rubble . . . or her mother. They tried to find work. Inflation made money

worthless. A friend of her uncle finally gave her a job in the ministry [government]

which paid the workers in potatoes and bread. They lived in a room open to the

elements; bombs had destroyed the windows and doors.

Ferry convinced Susan to go with her, Katherine, and two

Sabra (Israeli) agents who were attempting to get fifty Polish Jewish children

to Israel. The children had survived by hiding in Christian homes. Susan and

her friends rode with them by train to the Hungarian border where they had to

walk about 200 miles.

The friends, with the two Sabra agents and three other men,

accompanied the children through heavy snow in the fields and woods. Twice,

they paid off Russians who stopped them, but the third time, at the German

border, they had to make a run for it. They abandoned all their belongings in

their dash for freedom. Older children carried the younger ones. Russian

bullets followed them. Once safely across, the children continued through

Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Cyprus and then into Israel. But Susan still did

not want to go to Israel.

Later, Susan said she regretted that decision and felt pride

in what Israel stood for. “You know, even if you have to die, if you die on

your feet fighting, it’s a heck of a lot different than to be shoved into a gas

chamber [to] die like mice or cockroaches, or whatever.”

Susan lived in Germany for three years, then married a GI

and came to America in 1948, becoming a U.S. citizen. She had two children,

Diane and Leslie, and lived on Long Island, NY. Struggled with multiple health

issues, she worked in various factories to pay her medical bills before getting

a clerical job on Mitchel Air Force Base, which turned into a civil service

career of 30 years.

She divorced and eventually married another serviceman. With

his transfer to Maxwell Air Force Base, they moved to Montgomery, Alabama.

Ferry and Katherine joined relatives in America, and the

three friends kept in touch for the rest of their lives. Finally locating her

mother, who had returned to Budapest, Susan brought her to Montgomery in

1956.

Susan Petrov Eisenberg died in Montgomery, Alabama, in 2008.

Note: I had the privilege of compiling Susan’s story. She was one of the survivors who made Alabama their home

after WWII. Others’ stories and a wealth of educational material about survivors and the Holocaust is available

at the Birmingham Holocaust Education Center website—bhecinfo.org

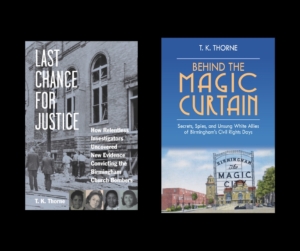

T.K. is a retired police captain who writes books, which, like this blog, go wherever her interest and imagination take her.